When you get your latest electronic toy -- iPhone, iPad, Xbox, Wii, Guitar Hero: Metallica, Playstation, Game Boy, Nintendo -- do you ever think about how many people died to put it in your hands?

Probably not. Human sacrifices (unwilling ones) in the course of bringing conveniences, amusements, and luxuries into our homes and hands are not the most natural thing that comes to mind when we enjoy a brand-new purchase. They’re not a particularly pleasant thought, either.

Yet many of our possessions today have come to exist through a process that included the waste of precious human lives. When slaves worked outside the door (and sometimes inside a well-to-do household), and slave-trading ships carrying more cheap labor from Africa lost and dumped up to a third of their human cargo on the voyage across the Atlantic, this was a little more obvious.

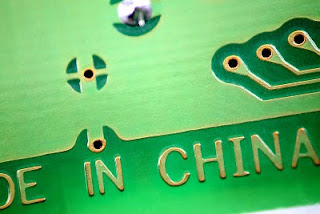

Today, the truth becomes evident only once in a while … such as with the recent rash of suicides among workers in the Chinese factories that make iPhones.

This year, at least 12 assembly-line workers, many of them young women, have committed suicide at Foxconn plants in China, and at least two more have attempted to kill themselves. The most recent “successful” attempt was on August 4 when a 22-year-old woman leaped to her death from her factory dormitory.

Foxconn is the registered trade name of Hon Hai Precision, the primary manufacturer of iPhones and iPads for Apple. A Hon Hai company spokesman said Friday that it had been “blinded” by its success, and didn’t cater to the emotional needs of its young workforce, of which 75 percent is between the ages of 18 and 24.

The company has responded by doing everything from installing nets around its buildings to catch falling workers, and holding morale-boosting pep rallies, to announcing a 20-percent pay raise in May. An entry-level worker at the company’s Longhua plant was reported to make 900 yuan, or $131.80, a month before overtime or bonuses.

Suicidal pressure and deadly working conditions are nothing new, even in the U.S. The old phrase “a Chinaman’s chance” (meaning slim to none) dates from just after the Civil War when Chinese workers on the transcontinental railroad in California, Nevada, and Utah were lifted up or down rock cliff faces in baskets to set dynamite charges for construction of the transcontinental railroad. Many of them fell or were accidentally blown up.

When my wife and I investigated her ancestors in southwestern Pennsylvania, I noticed that local newspapers from the late 19th and early 20th century were full of stories of fatal coal mining accidents. These workers were digging coal to fuel trains, steamboats, and factories, and to heat homes. Dead white miners were usually identified by name, but only numbers were provided for foreign immigrant fatalities.

There’s been plenty of talk about American jobs outsourced to overseas locations. We’ve also exported some of the employee fatalities that are also an inherent factor in industry -- diminished in more recent decades by detested government regulation.

(On the flip side, one might also note that suicide rates go up among unemployed Americans; an August 17 news report in the Washington Independent noted skyrocketing suicide rates in high-unemployment areas such as Elkhart County, Indiana and Macomb County, Michigan.)

I’m not saying any American consumer desires or expects such deaths. There isn’t really anything the buyer at this end of the process can do about them. But it behooves us to be aware of how interconnected we really are in the developing global economy, and that no “free market, individual rights” argument is going to overcome the fact that what people do (or buy) on one side of the planet can affect, and be affected by, events on the other.

That’s a fact of life today. And death.

No comments:

Post a Comment