I saw Harlan Ellison in a more conventional setting the following year. It was a lecture at MIT, at the other end of Cambridge. I remember he took a while to tell much of the story about the anguish of dealing with moronic movie producers while working on his screen adaptation of Asimov’s I, Robot a few years before.

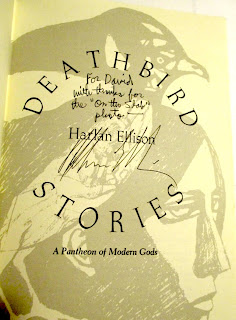

During the autograph session afterward I handed him a print of the photo I’d taken of him at his typewriter at the Sheraton Commander the year before, and he thanked me in a personalized signing of my first cloth edition of Deathbird Stories.

Around the same time, I was lucky to see the pair of artists who had done so many covers for Ellison as well as the inner illustrations for the Dangerous Visions series. Partners in art and life, Leo and Diane Dillon came to Boston on tour. I bought a copy of the most recent coffee-table children’s book they’d illustrated, Jan Carew’s Children of the Sun, but also had them sign their names next to Harlan’s in my first edition of his most recent collection that carried their cover art, Shatterday.

In the summer of 1987 I left Boston to return to my home state of Oregon. I landed a job as a reporter for the daily paper in Roseburg, and settled in to cover local news, write concert and film reviews, and compose occasional hell-raising op-ed columns for fun, practice, and the angry letters to the editor they brought in.

Those were the days when I rarely encountered anyone who was acquainted with my favorite band, Gentle Giant, or the writers I loved most, such as Peter Matthiessen, Timothy Findley, and Ellison. At some point in 1989 or 1990, I gave a lecture at the Douglas County Library to introduce listeners to Harlan’s work, and I think the librarians were inspired to order copies of several of his books for the collection.

I talked about the raw power and imagination of a writer who could occasionally be sloppy about dates, facts, and references. When the novelist and writing teacher John Gardner (the American author of Grendel, The Sunlight Dialogues, In the Suicide Mountains, and Mickelsson’s Ghosts — NOT the British John Gardner who wrote spy thrillers, including James Bond continuations and several fine Sherlock Holmes pastiches centered on Moriarty) picked on a passage from an early Ellison book as an example of bad writing in Gardner’s 1983 book The Art of Fiction, I was annoyed on Ellison’s behalf.

With the advent of the Internet in the early to mid 1990s, activity picked up again. Various Usenet discussion groups devoted to science fiction sprang up, and eventually one called alt.fan.harlan-ellison. Some of the other longtime fans I would meet in person over the years and continue to talk with on Facebook I first “met” there.

White Wolf, a Georgia-based publisher of role-playing and fantasy games that must have made some serious money, announced it was going to republish the entire works of several iconic writers, including Fritz Leiber, Michael Moorcock, and Ellison. The idea would be to bind a pair of his older books in each volume with all-new cover art.

The end result was projected to fill 31 volumes. I’m sure I was not the only fan who, well aware of the author’s many past fights with publishers who had mishandled his work in the past, smirked to myself and thought: I wonder how long this will last? (As it turned out, the answer would be: just four volumes.)

Volume I of Edgeworks hit the streets in May 1996, comprising (appropriately) the fairly early (1970) story collection Over the Edge, and essays that had initially appeared mostly in L.A. Weekly between 1980 and 1983 under the title “An Edge In My Voice” — first collected in book form in 1985. The White Wolf edition was beautiful: solid, weighty, with an evocative illustration by a new artist, Jill Bauman.

BUT . . . it was a shambles in terms of the text. Misspelled words turned up every few pages. Another regular error my proofreader’s eye caught were double spaces between words in the middle of sentences. I was appalled.

Volume II, published in November 1996, collected Spider Kiss and Stalking the Nightmare and was no better. I noted that Steven Seagal’s name was misspelled, and fricassee was wrong, on p. xxxv. Even more obvious, in the sixth paragraph of chapter 6, “gstalt” and “teh” (instead of “the”) turn up. Even a non-proofreader would have noticed those. A few pages later, on page 47, Shelly Morgenstern says “I’ll take a look a look on the kid.”

In Stephen King’s Foreword to the second half, one finds the phrase “… preserved between the boards of one of this admirable book.” Even foreign phrases you’d think a person would have to check, such as “rictus sardonius” (which is how it appeared in chapter 20) made it into the First White Wolf Omnibus Edition.

Since they’d done this twice in a row, I felt the need to step up. I wrote Harlan a letter to say “you and your work deserve better.” I don’t think I kept a copy, but I’m sure I pointed out an array of egregious examples from the first two volumes and offered to proofread the next White Wolf volume for free.

Although I’d seen him read and speak in public twice — in Cambridge 13 or 14 years before — and I’d interviewed him briefly over the phone in 1984, from his point of view I was still nothing more than a fan. I doubt my name would have meant anything to him even by the late 1990s.

Ellison called me at home (I think on the first try he got my wife Carole) and said he would “try me out” on this one, and if he liked my work, he might have me do more and pay me the next time. So in the winter of 1996/97 I went through the galley proofs for Edgeworks 3 — which combined The Harlan Ellison Hornbook (a series of essays that had originally appeared mostly in the Los Angeles Free Press and Los Angeles Weekly News in 1972 and 1973) with Harlan Ellison’s Movie, a screenplay commissioned by Marvin Schwartz and written about 1970.

For pro bono labor, this was highly enjoyable work, given that the Hornbook is wildly peripatetic and veers further into personal content than the “Edge In My Voice” columns, which tended to stay closer to political and film/TV industry topics. I still have the 2-1/2-inch stack of laser-printed proof pages the publisher FedEx’d to me at Harlan’s insistence on Dec. 27, 1996 which I proceeded to mark up with a red pen . . . as well about 10 pages of notes I faxed to the White Wolf team between Jan. 16 and Feb. 6, 1997.

Looking back over them and comparing my first-edition copy, I’m reminded that White Wolf rushed to publish in May without doing everything I advised. For example, the global coordinates in the second paragraph of Harlan’s introduction, “The Lost Secrets of East Atlantis” on p. xvii, still have curly apostrophes for the latitudinal and longitudinal minutes.

Looking back over them and comparing my first-edition copy, I’m reminded that White Wolf rushed to publish in May without doing everything I advised. For example, the global coordinates in the second paragraph of Harlan’s introduction, “The Lost Secrets of East Atlantis” on p. xvii, still have curly apostrophes for the latitudinal and longitudinal minutes.

(The proper vertical marks — ' and " — are known as a prime and double prime. Before computers came along, most manual typewriters offered only these options for apostrophes and quotation marks. Perhaps (if you’re older than, say, 50) you might recall that certain typewriters made you type a prime, then back-space and type a period below it to create an exclamation point. Later, dot-matrix and early computer word-processing programs did the same. Now that most computers offer all the options in their massive toolbox of fonts, everyone ought to take advantage of primes and use them to indicate geographical minutes and seconds, as well as feet and inches — as in, I am 5' 10" tall — so “smart” or “curly” apostrophes and quotation marks may retain their own identity and do their job. A lot of Internet-age babies don’t know the difference, however, so you’ll see primes all over websites even now. I’m nitpicky, which is what makes me such a good proofreader and editor.)

In the second paragraph of Installment 10, “The Day I Died,” ’67 Camaro still has a hash mark for what SHOULD be an apostrophe . . . but at least it isn’t an open quotation mark — as in, ‘67 Camaro — which is what I caught in the galley proof. These are just a couple examples of screwups that ran to the dozens.

As I stated above, Harlan was a great raconteur — a storyteller par excellence. But he didn’t always get every detail right. That’s not such a big deal when your task is to stir and entertain an audience with a fantasy story or screenplay . . . but in nonfiction on the page — and especially when you’re quoting someone with attribution — you ought to get it right. That’s where nitpickers like me come in.

Before Edgeworks 3 went to press, I noticed instances where Harlan misquoted Michigan J. Frog, Pogo, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I assume the quotes were wrong in his original newspaper columns, but I have not seen copies of those. They were certainly wrong in the first book edition (the Penzler), and the errors were copied into the White Wolf galley proofs, where I saw them.

You remember Michigan J. Frog, don’t you? He’s the singing, dancing amphibian in the 1955 Warner Bros. Merrie Melodies cartoon directed by Chuck Jones, “One Froggy Evening,” who pops out of a box inside the 1892 cornerstone of the demolished J.C. Wilber Building, pulls up a top hat and cane, and proceeds to dance and sing . . . what?

In Hornbook installment 23, dated April 19, 1973, Harlan renders it as “Hello, my honey, hello, my baby, hello my ragtime gal….” I sensed that wasn’t right because my Dad used to sing the phrase to himself when I was a kid in the Sixties. It was “Hello, my baby, hello, my honey, hello, my ragtime gal….”

Sure, it’s a small thing, but when a cultural reference is that famous (and since the advent of YouTube, so readily available), it’s going to clang on a lot of readers’ ears if you switch the words around. Worse, the song’s very title — a Tin Pan Alley composition by Joseph E. Howard and Ida Emerson dating back to 1899 — is “Hello Ma Baby.” And the frog reprises it exactly the same way in the climax of that two-and-a-half-minute classic, in the year 2056.

I’m a little surprised that the first time Harlan misquoted Pogo and Dr. King, in an essay he titled “The Song the Sixties Sang,” the venue was Playboy magazine, whose fact checkers should have caught them. At the climax of that piece, Harlan cites a short list of ringing phrases from the decade he wishes to honor. Smartly, he notes the perennial confusion over what Neil Armstrong really said after stepping on the moon in 1969 — with some well-placed brackets: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

But here are the two final quotes in that list:

— Pogo: “We have met the enemy, and they are us.”

— Martin again, and last, and always: “Free at last! Free at last! Great God a-mighty, I’m free at last!”

Now, the Pogo citation is grammatically correct, but it’s a misquote that fails to reproduce the dialect of Walt Kelly’s southern swamp critters. Perhaps Harlan confused the Pogo/Walt Kelly line with the historic phase they were parodying: Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s triumphant report to General William Henry Harrison at the conclusion of the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812, “We have met the enemy, and they are ours!”

Pogo’s version was in fact “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” Many years earlier, in 1953, Walt Kelly did write something very close to it, in the introduction to The Pogo Papers:

Pogo’s version was in fact “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” Many years earlier, in 1953, Walt Kelly did write something very close to it, in the introduction to The Pogo Papers:

Traces of nobility, gentleness and courage persist in all people, do what we will to stamp out the trend. So, too, do those characteristics which are ugly. It is just unfortunate that in the clumsy hands of a cartoonist all traits become ridiculous, leading to a certain amount of self-conscious expostulation and the desire to join battle.

There is no need to sally forth, for it remains true that those things which make us human are, curiously enough, always close at hand. Resolve then, that on this very ground, with small flags waving and tinny blast on tiny trumpets, we shall meet the enemy, and not only may he be ours, he may be us.

The classic “We have met the enemy, and he is us” first appeared on a poster Kelly designed for the first Earth Day in 1970, and he placed it in the mouth of Pogo, the Okefenokee opossum, the following year.

As for the ringing final words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963, he too was quoting something else: an African-American spiritual. I don’t know the song, and we can debate whether King said “a-mighty” or managed to get out “almighty” out . . . but clearly, he says “Thank God,” not “Great God….”

As you’ll find in your copy of Edgeworks 3, I managed to get the quotes by Michigan J. Frog and Pogo corrected, but not Dr. King’s. Two out of three isn’t too bad, I guess.

* * * * *

[ Coming up, dining with Harlan in Oregon in 2001, indexing the Teats while recovering from knee surgery, and pushing a dead 1947 Packard down La Brea Avenue in Los Angeles. . . . ]

If you haven’t read them yet, here’s The Harlan Ellison Non-Interview, circa 1984

and my 1981 Cambridge, Massachusetts memory of Harlan writing and reading

No comments:

Post a Comment